India’s chief economic advisor has recently criticized Indian companies for making sudden changes in employee compensation despite 15 years of high profitability. He warns that we will be stuck in a self-defeating spiral of falling demand.

This highlights a sharp decline in real GDP growth of 5.4 per cent in Q2 FY25 versus the official forecast of 7 per cent for FY25 and concerns over a shrinking urban middle class. This is in response to comments from companies.

The CEA’s criticism contrasts with the official position a year ago, which attributed the contraction in household savings to increased household confidence in future incomes and employment.

This paradoxical shift towards charging them with inadequate remuneration therefore reflects growing concerns about a setback in aggregate demand for India’s growth prospects. Until now, companies have been criticized for lacking capital investment despite supply-side benefits and surging generous profits.

Causation of deceleration

Given the change in stance, it is appropriate to assess whether the economic slowdown is due to weaker demand due to lower rewards, or whether we are barking up the wrong tree.

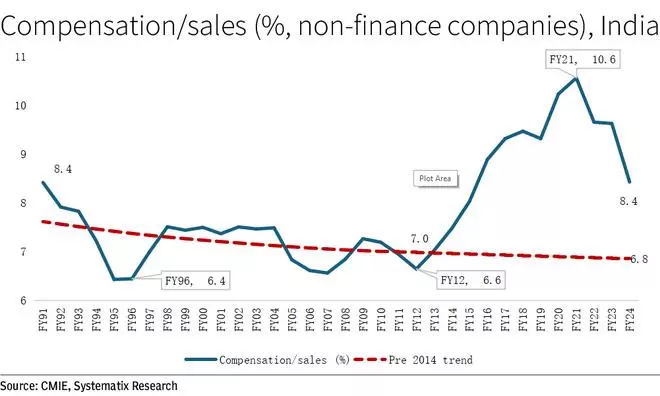

As demand visibility tends to increase, companies hire more resources, such as talent and capital. Similarly, compensation will also slow as companies are slow to respond to slowing sales growth. This slow response was exacerbated during the period of structural sales growth up to fiscal 2014. Since then, it has declined considerably.

Private non-financial companies (CMIE sample) had an increasing trend in sales and compensation growth from 2006 to 2014. The 10-year CAGR in revenue accelerated from 12.4% to a peak of 17%, and compensation growth also accelerated from 11% to 17.5%.

However, since 2014, revenue growth has slowed to 8% (10-year CAGR), which is more than compensation growth has slowed to 10.7%.

In the structural upward trend of corporate performance from FY1991 to FY2014, the ratio of compensation to sales decreased structurally from 7.6% to 7%. However, during the slowdown phase, it consistently rose to 9.3% in FY2019. The 8.4% in FY24 is slightly lower than the pandemic-era peak of 10.6% in FY21, reflecting a temporary recovery in corporate sales.

Therefore, given the current high compensation-to-sales ratio, it is unacceptable to blame underpaid workers for the decline in demand in urban areas.

It is also misplaced to juxtapose slowing compensation growth with high profits.

The latter is related to firms’ exploitation of market share gains through monopolistic pricing brought about by various policies that promote supply-side fiscal stimulus and regularization, such as tax cuts and infrastructure investments.

Spending on compensation, on the other hand, is a function of capacity utilization and sales prospects, and is undermined by an accentuated K-shaped trajectory characterized by a thin upper arm and a heavier lower arm.

lack of demand

Latest data shows demand outlook continues to be lacking, with sales growth slowing to 3.5% in the first half of 2025, near the lowest level of the coronavirus pandemic, compared to the 10-year average of 8.4% in 2025 This is the lowest level in years. The most likely outcome, therefore, will be for compensation growth to slow further while companies continue to invest in capital-deepening technologies that increase labor redundancy. The rise in tax rates on households due to efforts to improve fiscal health has also worsened the demand situation, contributing to the slump in employee compensation.

Importantly, these trends are increasing, as evidenced by increasing ruralization, increasing worker dependence on agriculture (PLFS), and shrinking real income per worker (5-year CAGR of -1.6 percent, KLEMS 2024). This was preceded by a widespread income crisis. Declining value addition in the unorganized sector (ASUSE, 2015-2023) and setbacks in household savings.

Thus, prior to the recent concerns raised by corporate comments, demand slump despite the post-pandemic rebound in truncated urban demand and leveraged consumption camouflaging persistent household vulnerabilities. has been revealed as a long-term weakness in rural demand.

The issue of consumption demand is therefore much broader than just urban areas and requires an evaluation of policy options. At first glance, the landscape is confusing with multiple constraints.

household income The country, which accounts for 78% of GDP, has been affected by a contraction in real workers’ incomes.

demand is weak And the decline in profit margins will likely exacerbate the slump in private capital investment.

Decrease in profits Even though indirect tax collections have slowed, employee compensation is impacting direct tax collections.

financial impasse It has an impact on government spending. Mainly due to reductions in capital investment (-15% compared to the previous year), the rate slowed to 3.3% compared to the previous year (fiscal year, October 2017), the lowest level since fiscal 2009.

RBI guidance The improved outlook centers on gradualism with improvements in agriculture and government spending, following a downward revision of the FY25 GDP growth forecast to 6.6% (-60bp).

Rupee/dollar stability The leeway was created by the RBI’s drastic reduction in foreign exchange reserves. The potential for rapid declines could limit the ability to generate dividends to the government.

influence of The impending protectionism associated with Trump 2.0 has not yet played out.

80% from peak Considering credit deposit ratios, normalization of the banking sector means limited support for growth.

Entangled restraints are typical of constrictor knots, and disentangling them can be a long process. In the short term, we can expect the following combination of quick fixes and countercyclical responses:

Greater emphasis on local spending, resulting in less government capital investment. The increase in banks’ unsecured lending limits for agriculture signals a retreat towards directed lending.

Following the increase in capital gains tax, the proposal for an additional 35% GST slab on goods and luxury goods heralds an increase in the tax burden on the wealthy to shore up tax revenue.

GoI constraints are also enforced by the global listing of G-Sec. Therefore, financial support from various forms of minimum income schemes is funneled through the national budget.

If the central bank’s restrictive policy stance is the cause of the economic slowdown, it may be forced to ease policy interest rates prematurely. However, there is a risk that this could lead to a resurgence of inflation and exchange rate fluctuations, which could hinder growth.

India’s growth projections appear to face various constraints. Therefore, it may be misplaced to blame only companies. A review of structural policies is urgently needed to rebuild the growth buffer. This includes addressing increasing regionalization, spurious unemployment and income vulnerabilities through detailed strategies to create productive jobs in high-employment resilient service sectors and small and medium-sized enterprises, and household finances. This would include lowering the tax rate on the government, a progressive tax system, and breaking away from the current system. A “national champion” approach to expanding private investment mandates.

The author is Co-Head of Equities and Head of Strategy and Economics Research at Systematix Group. views are personal